Can you change your gut microbiome without swallowing a single microbe?

For years, we’ve told a fairly tidy story about the gut microbiome.

You eat microbes.

You inhale microbes.

You touch microbes.

Some of them make it into your gut.

They do useful things.

It’s a clean, mechanistic narrative. Comfortingly simple. Very on brand for modern biomedicine. But almost certainly incomplete.

To be clear, the blog title is a little misleading. We probably swallow millions of microbes every day. Most of them, however, never establish residence in the gut, blocked by immunological, chemical and ecological barriers. But this raises a more awkward question. What if the gut microbiome is shaped more by what happens around the body than what enters it?

What we see.

What we hear.

What we touch and smell.

How we feel.

How our nervous system handles stress.

We evolved in environments that talked to our bodies constantly

For most of human history, our nervous systems didn’t live in offices, cars or scrolling rectangles. They lived in multisensory natural landscapes. Wind through leaves. Diverse birdsong with structure and variation. The smell of damp soil after rain or oils from plants. The visual fractals of trees, coastlines and clouds. Hands in dirt. Food eaten slowly, socially, contextually. Those inputs were information. And our biology – especially our stress systems and immune systems – evolved to respond to them.

Fast forward to now. We’ve stripped away much of that sensory dialogue and replaced it with noise, light pollution, chemical exposure, monotony and chronic cognitive and emotional load. And we seem surprised as a society when stress-related diseases, immune dysregulation and gut problems explode.

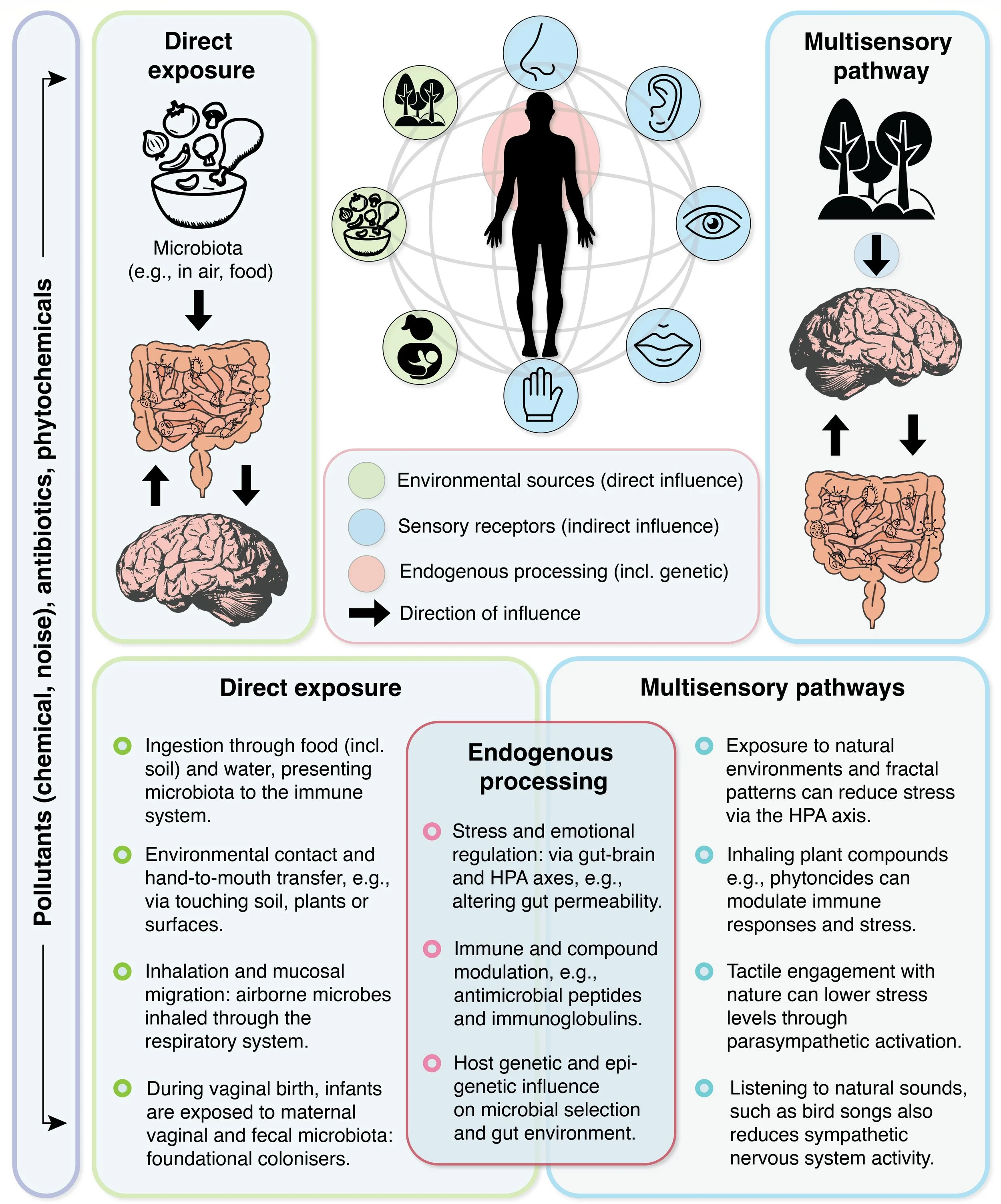

In a recent paper, we asked, What if nature shapes the gut microbiome indirectly –through the nervous system, immune system and gut–brain axis – rather than only through direct microbial transfer?

There’s a critical window early in life – roughly the first three years – when the gut microbiome is highly malleable. During that time, direct microbial colonisation matters enormously. Birth mode. Breastfeeding. Early diet. Environmental exposure. All of it. But in adults? The evidence for long-term colonisation by environmental microbes is surprisingly weak. Yes, you ingest and inhale millions to billions of bacteria every day. Yes, gardening may temporarily increase overlap between soil microbes and the gut. But in most cases, those microbes don’t stick around. They pass through. Which raises a question: If adult gut microbiomes do change after nature exposure – and they appear to do so – what’s actually driving that change?

Stress, immunity and the gut are in constant conversation

We know that stress alters gut permeability. We know cortisol reshapes immune signalling. We know parasympathetic activation affects gut motility, mucus production and microbial niches. We know that microbes, biogenic compounds and even parts of microbes can all trigger immune responses. We know inflammation favours some microbes and suppresses others. And we also know that nature exposure reduces stress physiology. It can lower cortisol, increase parasympathetic tone, reduce inflammatory cytokines, and improve immune regulation.

So, even if no new microbes permanently colonise your gut, the conditions inside your gut can change in response to these stimuli. And microbes ‘care’ about conditions. Change the environment, and the ecosystem responds.

One of the most underappreciated aspects of this story is that the body responds to meaning. The limbic system doesn’t ask whether a tree is ‘just visual input’. Your nervous system and immune system react to perceived safety or threat. It’s why natural soundscapes, for instance, calm the nervous system. And it all feeds downstream, into the gut. In other words, your microbiome is shaped partly by what your nervous system ‘believes’ about the world you’re in. And probably by how you process situations and emotions.

We are holobionts, not individuals

This paper also sits on something I keep coming back to – the holobiont perspective. You are arguably not just a human with microbes attached. You are a multispecies system. Your physiology, immunity, mood and behaviour are co-shaped by microbial partners that respond to diet, but also to stress, sleep, hormones, inflammation and neural signalling. Which means that when we talk about health – especially gut health – we can’t afford to ignore the sensory and psychological context of life. The reductionist model breaks down here.

If the gut microbiome is shaped through multisensory, immune-mediated, and neuroendocrine pathways, then public health strategies that focus only on diet or probiotics are missing something fundamental. The design and restoration of our living environments and social systems matter enormously. Access to biodiverse green and blue spaces matters. Noise and light pollution matter. How, where, and with whom we eat matters. Whether environments feel safe, coherent and alive matters.

The takeaway

After early childhood, your gut microbiome may be influenced less by the microbes you directly ingest – and more by the world your nervous system thinks you live in. That world can be hostile, noisy, synthetic and stressful. Or it can be rich, textured, biodiverse and regulating. Your microbes are paying attention either way. And if we want healthier humans, we may need to stop thinking only about what goes into the body – and start thinking much more seriously about what surrounds it. Because the gut isn’t just eating the environment. It’s experiencing it.

Check out our recent paper here: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/msystems.01107-25

For more on this interconnected thinking, check out my books: www.jakemrobinson.com/books