Walking Ecosystems

By Jake Robinson

Principles of ecology

I stood near a large pond in a forest, watching a small brown Daubenton’s bat chasing down mosquitoes freshly hatched from the stagnant waterbody. My mind wandered. I recalled echoes of an event that happened several years ago. I watched a cheetah chase down a reedbuck antelope on the African savannah, predator-prey dynamics across scales whirling around in my mind, from large mammals to bats and bugs. I then imagined wearing space-age goggles. I pressed the zoom button in this fantasy world, and voila, my vision was magnified over a million times. I steered my eyes towards the Daubenton’s bat, darting across the pond’s surface. I imagined peeking into the bat’s body at a microscopic scale. At the very moment the bat chased down the mosquitoes in the woodland ecosystem, strange alien spider-like viruses were chasing down bacteria inside the bat’s gut ecosystem. These are called bacteriophages—viruses that target and kill bacteria. My mind jumped back to reality, yet the only fantasy element of this story is the space-age goggles. Indeed, principles of ecology—e.g., predation, competition, cooperation, and energy flows—apply at myriad scales, including within the human body and the intertwined macro and microscopic ecosystems that we depend upon for survival.

Holobionts and the gift economy

We can view the human body as a holobiont—a host plus trillions of microbes working symbiotically to form a functioning ecological unit. We can also view the rest of the nature surrounding us as a vast collection of holobionts. We each emit a million biological particles every hour, sharing the invisible constituents (the microbes) of our human holobiont with all the other holobionts (the plants and animals) whilst they share their invisible constituents with us. “It’s an unseen and subconscious gift economy!” We must recognise this deep interconnectedness. Arguably, the natural step to follow this recognition is to “promote beneficial relationships between the constituents of the whole. The whole being the planet, and the constituents being our environments, our societies, our ‘selves’, our microbes, and our genes”. By doing so, we can foster mutually-advantageous relationships to benefit both the health of our human bodies and our surrounding ecosystems with their bountiful-but-dwindling biodiversity.

Microbiome-inspired green infrastructure

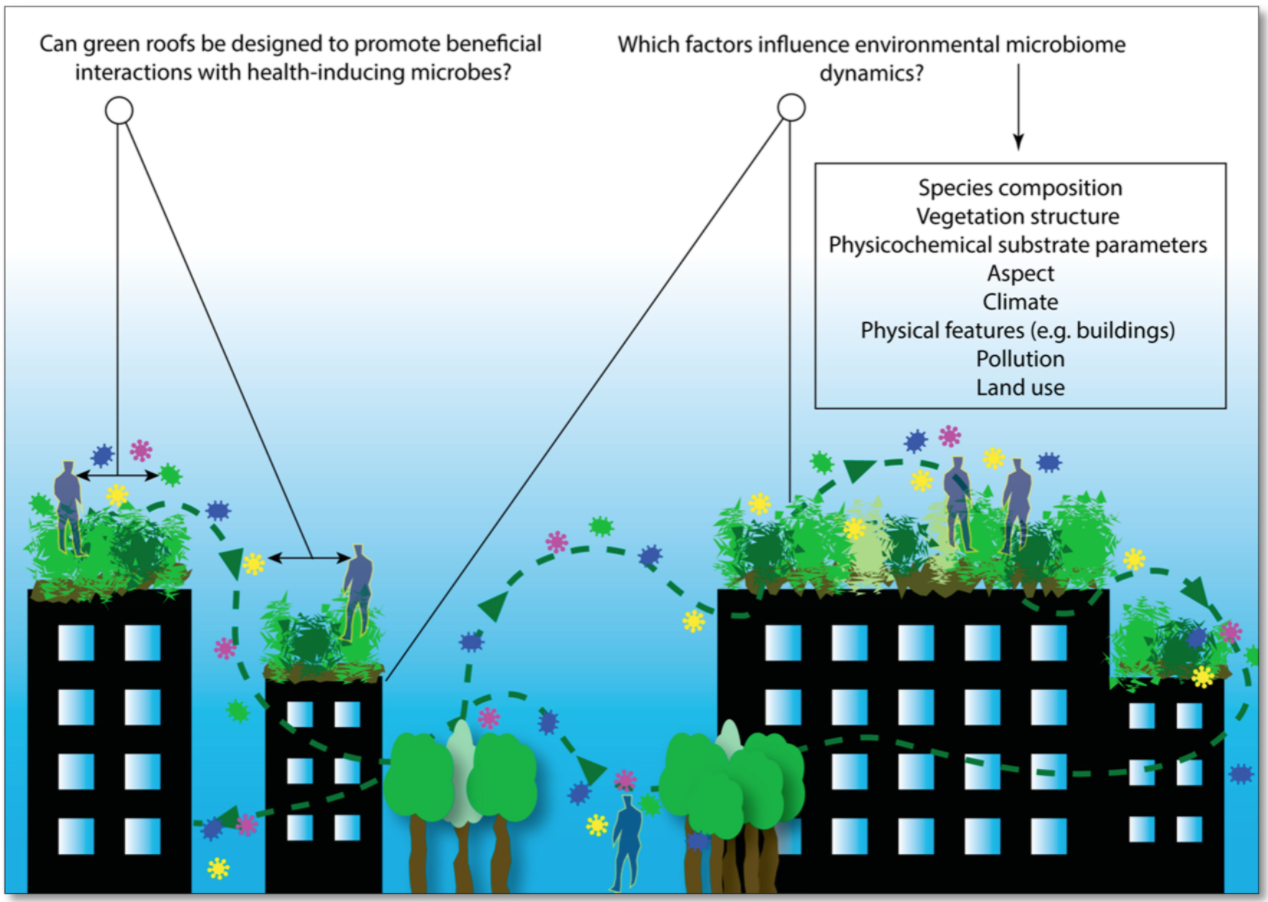

With this in mind during my PhD, I conceptualised Microbiome-Inspired Green Infrastructure or ‘MIGI’. “It is a collective term for the restoration, design, and management of living urban features that could potentially enhance the health of all urban dwellers and encourage more nature into our cities and our bodies”. I won’t go into too much detail here—this will be covered in future blog posts. But MIGI focuses explicitly on the need to consider microbes—the invisible biodiversity—when designing and restoring urban environments. This can include designing habitats to enhance exposure to our immune-boosting invisible friends whilst supporting wildlife or using ‘bio-integrated’ design to create building materials that support microbes, mosses, lichens and algae. The desolate concrete skins of our urban environments needn’t be desolate. I am convinced that applying principles of ecology to our urban environments and our bodies (i.e., our “walking ecosystems”) will help tackle connected human health and ecosystem issues globally. Halting and reversing dysbiosis in all its manifestations is an ambitious undertaking, but it can be done. This first PhD paper is a tiny nail scratching the surface of potential solutions—and there are many if we choose to work with nature.

Find out more about MIGI in future blog posts and in my forthcoming book Invisible Friends.

Read the full paper here: https://www.mdpi.com/2078-1547/9/2/40

Authors: Jake M. Robinson, Jacob G. Mills, and Martin F. Breed