The Holobiont Blindspot

By Jake Robinson

The way we think about how we think may need to be revisited.

Holobiont

A holobiont is a term popularized by the late biologist Prof. Lynn Margulis in the early 1990s. At a fundamental level, the term describes a host organism (e.g., an animal or plant) and its associated microbes. We as humans are host to trillions of bacteria, viruses, fungi and others that reside inside and on our bodies—our ‘microbiome’. It is said that the genes in our microbiomes outnumber our human genes by 150 to 1, as Ed Yong says: “I contain multitudes”!

Many of the microbes in our bodies are essential to our survival. For example, they regulate our immune systems, metabolise our food and provide nutrients. Moreover, there is rapidly growing evidence to suggest that our guts denizens might influence our behaviour, mood, and decision making via a communication system referred to as the microbiota-gut-brain axis. So, we could actually view ‘ourselves—that is, a human host plus its symbiotic microbes—as a collectively functioning ecological unit or a ‘holobiont’.

The Holobiont Blindspot

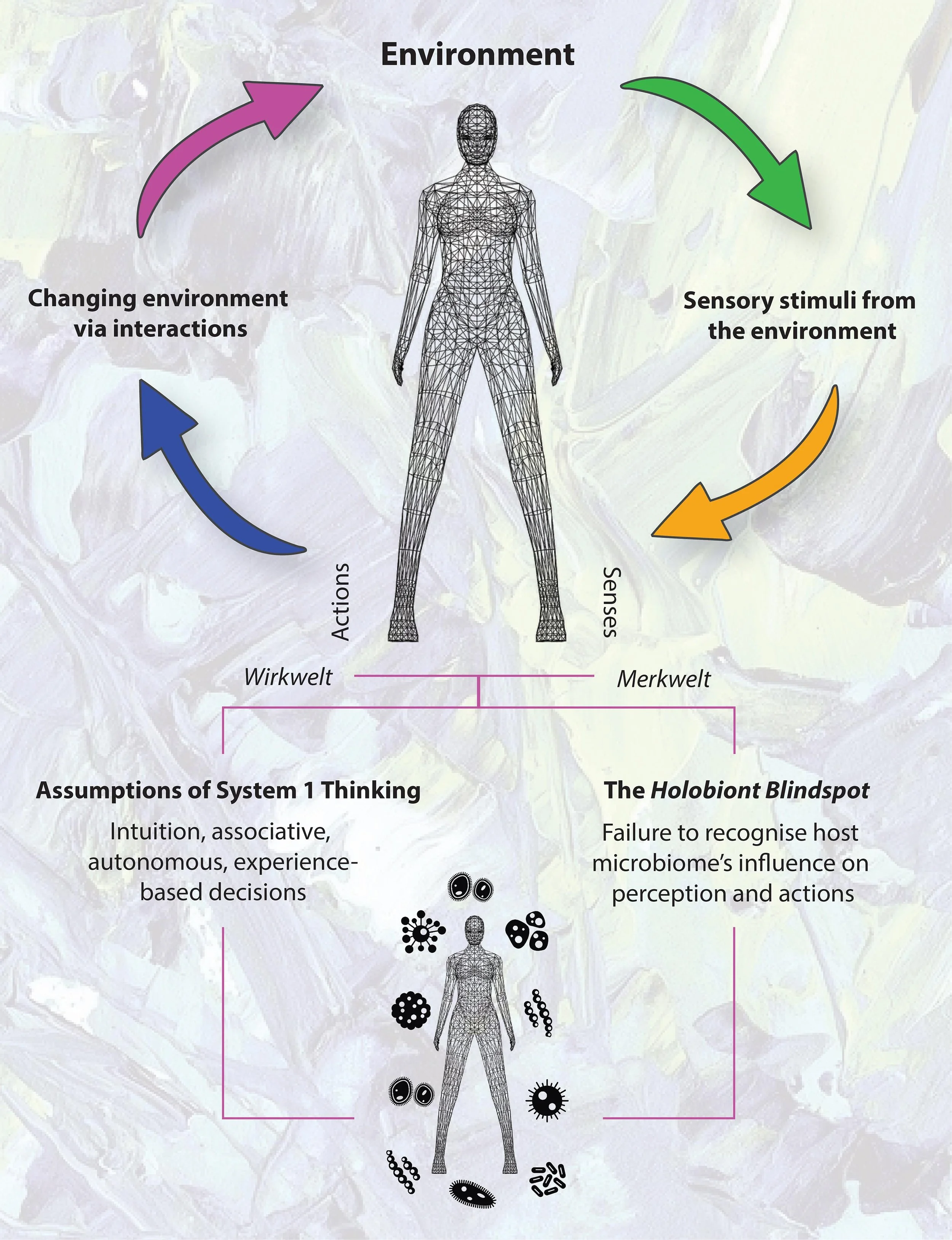

Just as cognitive biases (systematic errors in judgement) can manifest through the attribution of human-like behaviours to non-human animals (or plants, fungi etc.), treating holobionts as individual subjects divorced from any cognitive influence of microbial interactions with the body, the brain and the environment, could also be viewed in this manner. In other words, failing to recognise the role of host-microbiome interactions in animal and plant behaviour and decision-making underpins what we recently called the Holobiont Blindspot.

This blindspot could be viewed from either a first or third-person perspective. For example, the first-person perspective would involve recognising the microbiome’s influence on one’s own intuition/behavioural responses and even mental health. The third-person perspective could include a researcher studying animal populations with preconceived ideas about an animal’s behaviour without considering the microbiome’s influence. This could lead to delusive generalisations and inaccurate conclusions about a given behaviour.

Microbiomes have been shown to influence host mental health, sex hormones, memory and many other aspects associated with important social behaviours in animals. Therefore, could our microbes contribute to relationship issues, e.g., by changing preferences to human odour ‘attractants’, or by influencing memory recall—did you forget an important date recently?! We discuss this in detail in our paper. We also discuss this blindspot in relation to the ‘Umwelt’. This concept describes the contrasts in the sensory worlds of different species. The Umwelt can be divided into the Merkwelt (perceptual world) and the Wirkwelt (effector/action world) to define an animal’s sensory unit, from perception to behaviour. We suggest that microbially-driven host behavioural responses could augment the Umwelt concept by deeply considering the microbiome's role in the realms of perception and action.

“The very notion of intuition may need to be revisited!”

Intuition is a part of our cognitive system that Nobel Prize winner Professor Daniel Kahneman calls ‘System 1 thinking’. This describes our decisions based on impulse and associative memory. Imagine watching squirrels jumping from tree to tree in a forest. You intuitively know that one squirrel in the background is more distant than another squirrel in the foreground. This is System 1 thinking. However, you’d need ‘System 2 thinking’ to consciously calculate the approximate distance between the squirrels or between the squirrels and yourself. System 2 thinking is slow, calculative thinking. We propose that our microbial symbionts could affect System 1 thinking (our intuition) via the microbiota-gut-brain axis and/or olfactory processes. Indeed, the pathways and mechanisms to such behavioural manipulation have already been demonstrated in animal models.

Could our microbiomes affect our perceptions, actions, and intuition by regulating our impulses? Should this be considered when debating the ideas of determinism, free will, and responsibility? Research is needed, but the way we think about how we think may need to be revisited…unless our microbes have other ideas.

Find out more about the Holobiont Blindspot in future blog posts and in my forthcoming book Invisible Friends.

Read the full paper here: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.591071/full

Authors: Jake M. Robinson and Ross Cameron