The Lovebug Effect

By Jake Robinson

A jigsaw puzzle

A few years ago, I began wondering whether the microbial symbionts in our bodies might influence our decisions to spend time in particular environments. Professor John Cryan’s work on the microbiota-gut-brain axis influenced my thinking. So did Professor Graham Rook’s ideas on human–microbe co-evolution, the late E.O. Wilson’s work on biophilia, and Indigenous concepts of nature connectedness—our emotional, cognitive, and experiential connection with the rest of the natural world. These ideas were like pieces to a jigsaw puzzle beseeching to be slotted together.

We already know that intricate co-evolution has occurred between humans and microbes over many millennia. Our earliest ancestors are microbial. Even some of our organelles (“tiny organs” in our cells) originated from a symbiotic relationship when one microbe likely gobbled up another. Microbes have directly shaped the development of the mammalian immune system, and a whopping 8% of our DNA is viral in origin. The microbial genes in our bodies outnumber our ‘human’ genes by 150 to 1, and if you could extract the microbes from a single person’s body and line them up, they could circle Earth 2.5 times. It’s firmly within the realms of possibility that our resident microbes have a more profound influence on our day-to-day activities than we realise.

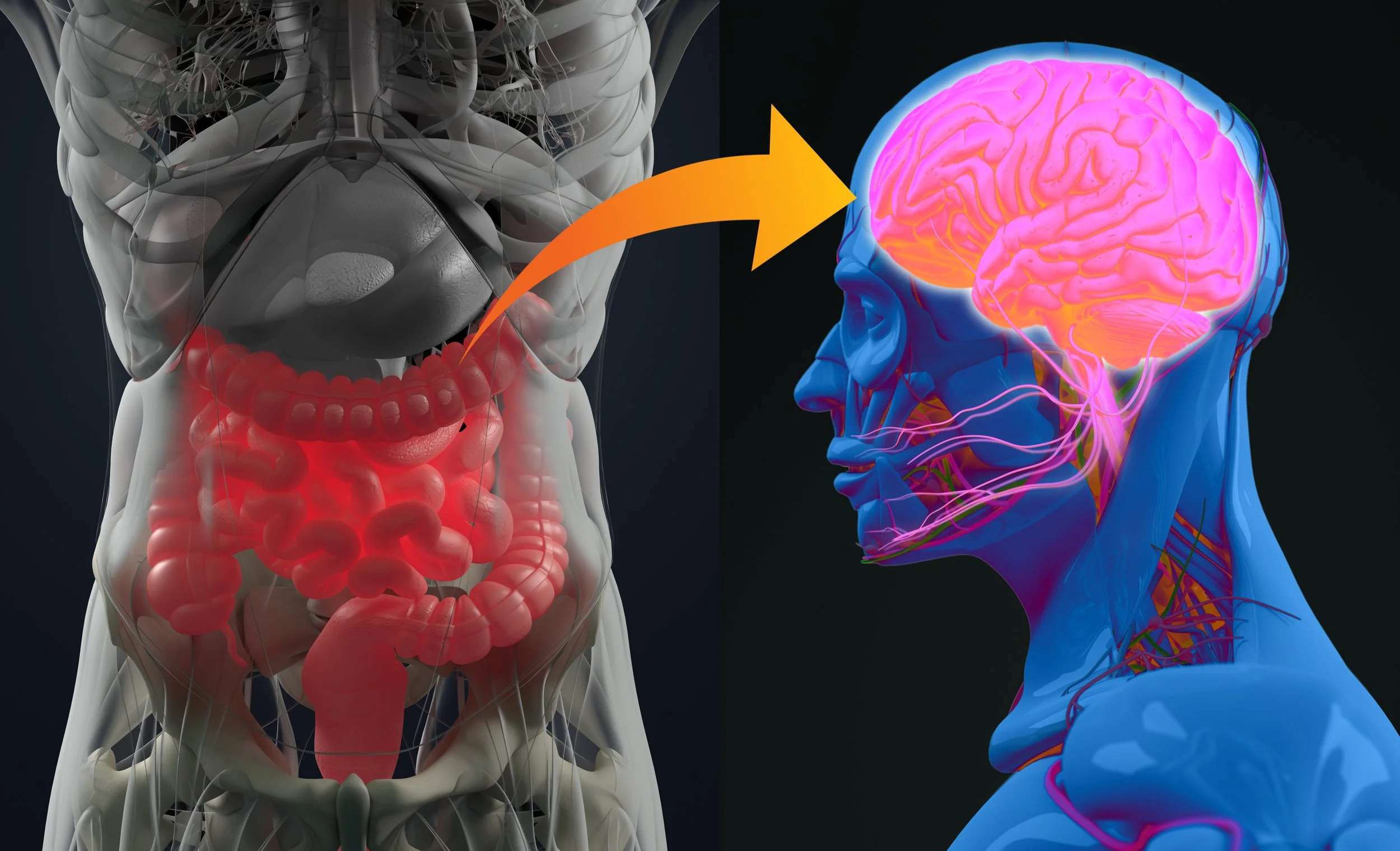

Microbiota-gut-brain axis

We now think microbes in the gut can talk to the brain via a two-way communication highway—like a motorway linking two megacities, but the cities are our vital organs. By altering our brain chemistry, microbes may be able to manipulate our behaviour—for example, to influence the food choices we make or our decisions to visit specific environments that benefit our body’s microbial ecosystem. Microbes have significantly influenced host feeding decisions and even sexual preferences in animal models. They can also tinker with the animal olfactory system (the part of the body responsible for processing smells), causing the animal to become averse to certain odours.

The Lovebug Effect

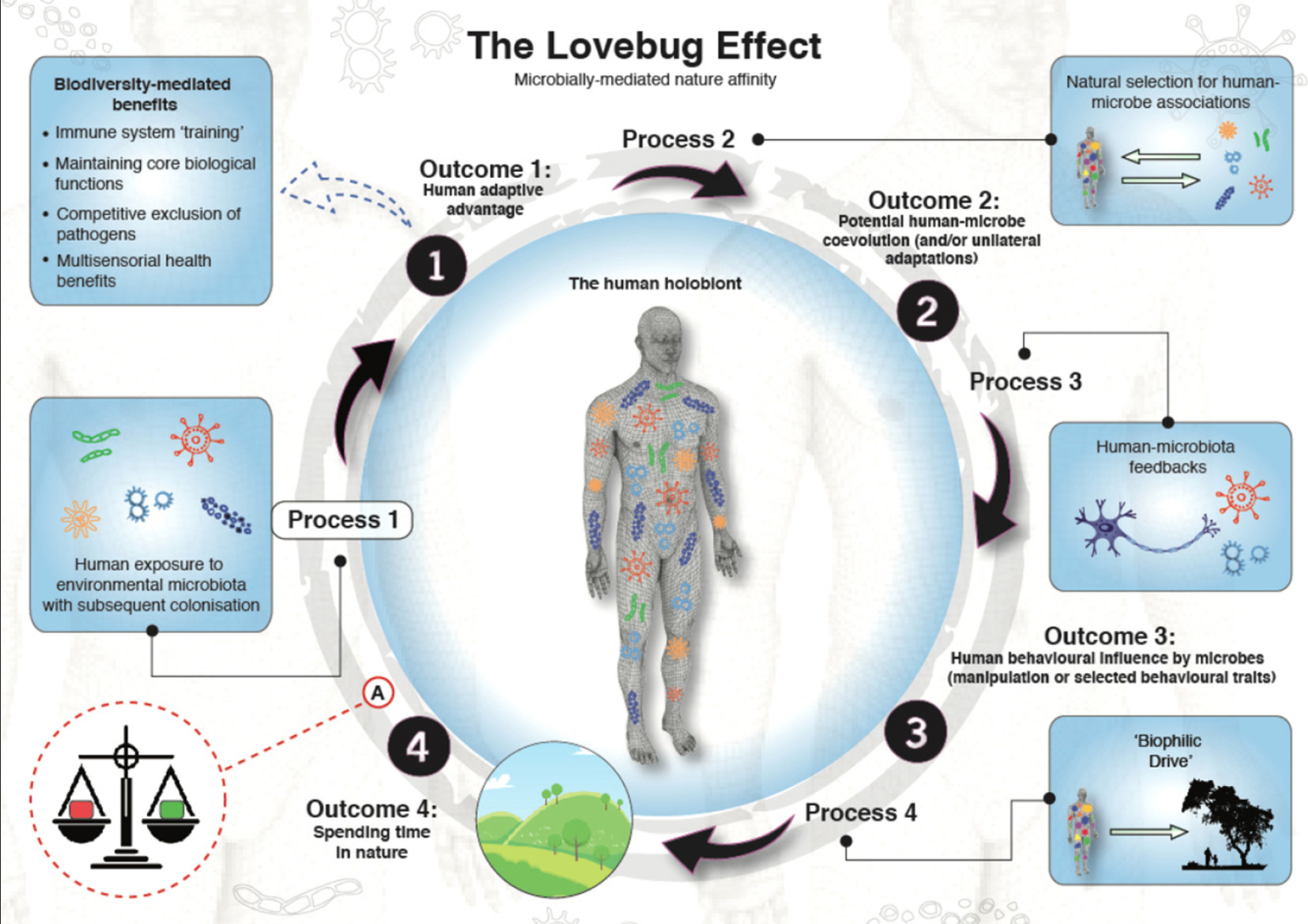

Bearing all this in mind, I developed a hypothesis/question: do our resident microbes influence our decisions to spend time in biodiverse environments? By doing so, the microbes could benefit by (a) recruiting other microbes and biological compounds from the environment that enhance the body’s microbial ecosystem, and (b) enabling the host to enhance their general health (by interacting with these health-promoting environments), thereby benefiting the microbes’ habitat, also known as the human body! I developed this idea with Dr Martin Breed. In 2020, we published The Lovebug Effect: Is the human biophilic drive influenced by interactions between the host, the environment, and the microbiome?

“Lovebug Effect translates to microbio-philia, from ‘bug’–a colloquial term for a microbe, and ‘philia’–from the Greek for love or attraction.”

When our walking ecosystems lack microbial species and interactions that sustain homeostasis (self-regulating stability), an evolutionary response might be to seek out invisible keystone species. However, in western society, our unhealthy diets, lack of biodiversity, overuse of antibiotics, and increased exposure to industrial pollutants, could inhibit the Lovebug Effect by causing chronic maladies such as autoimmune diseases and mental health issues. These conditions could lead to significant microbiota-gut-brain connection issues.

Our paper provides examples of behavioural manipulation at the hand of microbial symbionts and discusses why ecological restoration and halting the growing fear of microbes (aka Germaphobia) are vital.

Unlike the evolutionary processes in many animal and plant species, microbial evolution can be incredibly rapid. This occurs due to the ability of microbes to replicate at lightning speed. Some can even instantaneously transfer their genes into other organisms without mating in the traditional sense! This process is known as horizontal gene transfer. Due to this ability to rapidly evolve, if the selection pressures associated with the Lovebug Effect developed following the industrial revolution era (when biodiversity loss, antibiotics, and ‘extinction of experience progressed), microbial mutations could still occur in this short timeframe. This would help meet the demands of our rapidly changing internal microbial ecosystem whilst proliferating the microbes’ genes.

Some aspects of this article are likely to be controversial, but it is an important vehicle for generating discussion about how far microbiomes can go in terms of influencing human behaviour and health. If proven to be true, the Lovebug Effect could have important implications for our understanding of exposure to natural environments for health and wellbeing. It could contribute to an ecologically resilient future.

As Dr Nia Cason recently said in an article for Mental Floss, “other than stimulating curiosity, the Lovebug Effect serves to remind us of our deep-seated connection with the natural world – and that it’s in our best interests to conserve it.”

Find out more about the Lovebug Effect in future blog posts and in my forthcoming book Invisible Friends.

Read the full paper here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32146404/

Authors: Jake M. Robinson and Martin F. Breed